1992 Draft Defense Planning Guidance

last updated: February 20, 2020

Please note: The Militarist Monitor neither represents nor endorses any of the individuals or groups profiled on this site.

DPG Drafters and Consultants

- Dick Cheney

- Zalmay Khalilzad

- I. Lewis Libby

- Andrew Marshall

- Richard Perle

- Albert Wohlstetter

- Paul Wolfowitz

The 1992 draft Defense Planning Guidance (DPG), crafted by then-Defense Department staffers I. Lewis Libby, Paul Wolfowitz, and Zalmay Khalilzad, is widely regarded as an early formulation of the neoconservatives’ post-Cold War agenda, laying out a series economic and military objectives that were intended to ensure a U.S.-led unipolar global system. Although it was widely panned at the time, many of the ideas proposed in the document have persisted to this day, having played a particularly influential role in the wake of the 9/11 attacks and the launching of the “war of the terror.”

Since the election of Donald Trump, observers have recalled the importance of the DPG to U.S. security posturing. As one scholar noted in a 2019 New Republic article, although Trump has “stripped supremacy of ethical pretense and strategic justification” from the 1992 DPG formula, “the same basic strategy endures. … Our military dominance must be unquestioned,” Trump has declared, “and I mean unquestioned.”

The Origins of the Draft DPG

Under the auspices of then-Defense Secretary Dick Cheney, Libby and Wolfowitz, two of the few neoconservatives with posts in the realist-dominated administration of George H.W. Bush, were given the task of producing the DPG, a classified document that outlines U.S. military strategies and provides a framework for developing the defense budget. Because it would be the first DPG since the end of the Cold War, the officials had the daunting task of devising what essentially would be an entirely new framework for U.S. defense policy. In preparation for the drafting, the officials held a number of meetings with outside experts. Notable among the participants were Richard Perle, Albert Wohlstetter (former mentor to Perle and Wolfowitz), and Andrew Marshall, head of the Pentagon’s Office of Net Assessment (see James Mann, The Rise of the Vulcans: The History of Bush’s War Cabinet).

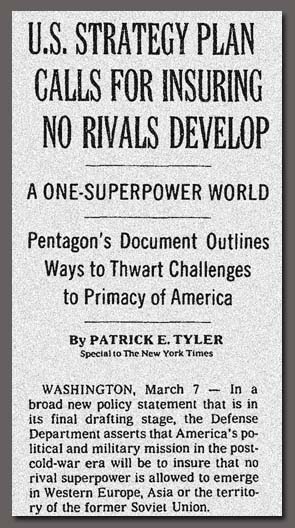

When the draft DPG was leaked to the New York Times and Washington Post, it created an uproar among Democrats and many administration figures, spurring the White House to immediately and publicly retract it. Among its more salient points, the draft guidance called for massive increases in defense spending, the assertion of lone superpower status, the prevention of the emergence of any regional competitors, the use of preventive—or preemptive—force, and the idea of forsaking multilateralism if it did not suit U.S. interests. It called for intervening in disputes throughout the globe, even when the disputes were not directly related to U.S. interests, arguing that the United States should “retain the preeminent responsibility for addressing selectively those wrongs which threaten not only our interests, but those of our allies or friends, or which could seriously disrupt international relations.” According to the draft DPG, the United States must also “show the leadership necessary to establish and protect a new order that holds the promise of convincing potential competitors that they need not aspire to a greater role or pursue a more aggressive posture to protect their legitimate interests.”

The guidance argued, “Our first objective is to prevent the reemergence of a new rival. This is a dominant consideration underlying the new regional defense strategy and requires that we endeavor to prevent any hostile power from dominating a region whose resources would, under consolidated control, be sufficient to generate global power. These regions include Western Europe, East Asia, the territory of the former Soviet Union, and Southwest Asia. There are three additional aspects to this objective: First the United States must show the leadership necessary to establish and protect a new order that holds the promise of convincing potential competitors that they need not aspire to a greater role or pursue a more aggressive posture to protect their legitimate interests. Second, in the non-defense areas, we must account sufficiently for the interests of the advanced industrial nations to discourage them from challenging our leadership or seeking to overturn the established political and economic order. Finally, we must maintain the mechanisms for deterring potential competitors from even aspiring to a larger regional or global role.” (For redacted versions of the original draft DPG and supporting documents, see the National Security Archive, February 26, 2008.)

Although rejected by the White House, the draft document had its supporters. Khalilzad told Mann that Cheney was impressed by it, allegedly telling Khalilzad, who was responsible for the actual writing of the DPG, “You’ve discovered a new rationale for our role in the world.” Neoconservatives outside government, like Charles Krauthammer, were also impressed. In a Washington Post column, Krauthammer asked, “What is the alternative? The alternative is Japanese carriers patrolling the Strait of Malacca, and a nuclear Germany dominating Europe” (quoted in Mann).

Nor did the draft 1992 DPG entirely disappear after the White House rejected it. According to Mann, the revised final version produced by Libby merely softened some of the hard edges of the earlier draft while preserving some of its core concepts, such as actively shaping the security environment, acting alone when necessary, and maintaining a dominant edge in military capabilities. Many of the ideas contained in the draft DPG were also revived repeatedly over the next decade, serving as a broad framework for building a new neoconservative consensus whose preeminent expression ultimately arrived in the form of President George W. Bush’s 2002 National Security Strategy.

Draft DPG Impact: From Bush Senior to Bush Junior

Almost 10 years after the draft DPG was rejected, George W. Bush entered the White House and shortly thereafter was confronted with the 9/11 terrorist attacks. Following the attacks, as the White House-led campaign to invade Iraq began to gain steam, many commentators began noting striking similarities between ideas emanating from the George W. Bush administration about its “war on terror” strategy and the ideas promoted by the Project for the New American Century (PNAC), a neoconservative-led pressure group created in 1997 to push a “Reaganite” U.S. foreign policy in the post-Cold War world. One of the first to report on this was Jim Lobe of the Inter Press Service (IPS), who in a December 2001 IPS article pointed out that the authors of the draft DPG were ensconced in the George W. Bush administration. Lobe reported that, “When he saw it [the 1992 draft DPG] shortly after the Gulf War ten years ago, Democratic Senator Joseph Biden, now chairman of the Senate Foreign Relations Committee, denounced it as a prescription for ‘literally a Pax Americana.’ The past, as is said, is prologue. At the time, Biden referred to a document by two relatively obscure political appointees at the Pentagon charged with drafting plans for U.S. defense strategy over the following decade. The authors now are back in key positions and their vision appears to be reviving.”

During the decade leading up to the election of George W. Bush, the ideas of the draft DPG were the subject of many neoconservative publications and advocacy campaigns, the most preeminent example of which was PNAC’s 1997 founding statement of principles. Like the draft guidance, the PNAC statement called for U.S. global leadership and preemptive action, arguing, “Of course, the United States must be prudent in how it exercises its power. But we cannot safely avoid the responsibilities of global leadership or the costs that are associated with its exercise. America has a vital role in maintaining peace and security in Europe, Asia, and the Middle East. If we shirk our responsibilities, we invite challenges to our fundamental interests. The history of the 20th century should have taught us that it is important to shape circumstances before crises emerge, and to meet threats before they become dire. The history of this century should have taught us to embrace the cause of American leadership.” Among the signers of this statement were Cheney, Wolfowitz, Libby, and Khalilzad. Other future Geor

ge W. Bush administration signatories included Rumsfeld, Peter Rodman, and Elliott Abrams.

In September 2000, PNAC published Rebuilding America’s Defenses: Strategy, Forces, and Resources for a New Century, a book-length report meant to serve as a guide for the next U.S. president in shaping the country’s security strategies. Authored principally by Thomas Donnelly of the American Enterprise Institute, with Donald Kagan and Gary Schmitt serving as chairmen of the study group that produced the report, Rebuilding America’s Defenses claimed that its principal source of inspiration was the 1992 draft DPG. The report’s introduction states, “In broad terms, we saw the project as building upon the defense strategy outlined by the Cheney Defense Department in the waning days of the [George H.W.] Bush Administration. The Defense Policy Guidance (DPG) drafted in the early months of 1992 provided a blueprint for maintaining U.S. preeminence, precluding the rise of a great power rival, and shaping the international security order in line with American principles and interests. Leaked before it had been formally approved, the document was criticized as an effort by ‘cold warriors’ to keep defense spending high and cuts in forces small despite the collapse of the Soviet Union; not surprisingly, it was subsequently buried by the new administration [of Bill Clinton].”

In the wake of 9/11, with many of the same people involved in promoting the ideas of the draft DPG now working in the Pentagon and the Office of the Vice President, the ideas found new life. In particular, when the administration released the unclassified version of the 2002 National Security Strategy, observers remarked on the many similarities between the draft guidance and the then-newly emerging “Bush Doctrine,” particularly their mutual call for a preemptive defense posture. As summarized by leading international relations scholar Robert Jervis, the Bush Doctrine is composed of “a strong belief in the importance of a state’s domestic regime in determining its foreign policy and the related judgment that this is an opportune time to transform international politics; the perception of great threats that can be defeated only by new and vigorous policies, most notably preventive war; a willingness to act unilaterally when necessary; and, as both a cause and a summary of these beliefs, an overriding sense that peace and stability require the United States to assert its primacy in world politics” (cited in Chris Dolan and David Cohen, Politics & Policy). In other words, the doctrine represented a distillation of core neoconservative goals, as outlined in the 1992 draft DPG and later in PNAC’s founding statement of principles and Rebuilding America’s Defenses.

Declassification of the Draft DPG Despite the well-documented connection between the draft DPG and the Bush administration’s policies, efforts to declassify the DPG and related documents has proved difficult. In February 2008, the National Security Archive (NSA) at George Washington University published a number of redacted documents, including the original draft DPG. However, a February 26, 2008 archive press release about the documents, which it received through a Freedom of Information Act request, said, “Remarkably, these new releases censor a half dozen large sections of text that The New York Times printed on March 8, 1992, as well as a number of phrases that were officially published by the Pentagon in January 1993.” Tom Blanton, director of the archive, said, “On close inspection none of those deleted passages actually meet the standards for classification because embarrassment is not a legal basis for secrecy.”

Despite the redactions, the declassified documents shed considerable light on the process that led to the creation of the DPG. The NSA’s press release said, “The documents recently declassified by the Defense Department in response to the Archive’s appeal provide an inside view of the making of the Defense Planning Guidance from September 1991 to May 1992, when Joint Chiefs of Staff Chairman Colin Powell and Under Secretary of Defense for Policy Paul Wolfowitz approved it. Writing in the wake of the Soviet Union’s collapse, the group of Republican-oriented officials that produced the Guidance wanted to preserve the unique position of American predominance that was emerging. With the leak of a draft in March 1992 and the resulting public controversy over the language about preventing a ‘new rival,’ ‘Scooter’ Libby and his colleagues recast the document so that it would pass public scrutiny while meeting Richard Cheney’s requirements for a strategy of military supremacy. Believing that military spending at Cold War levels was no longer possible, Cheney and his advisers wanted to develop lower-cost strategies and plans to prevent future global threats to American power and interests.”